Felix Mitterer

“Call, Call, Vienna Mine“

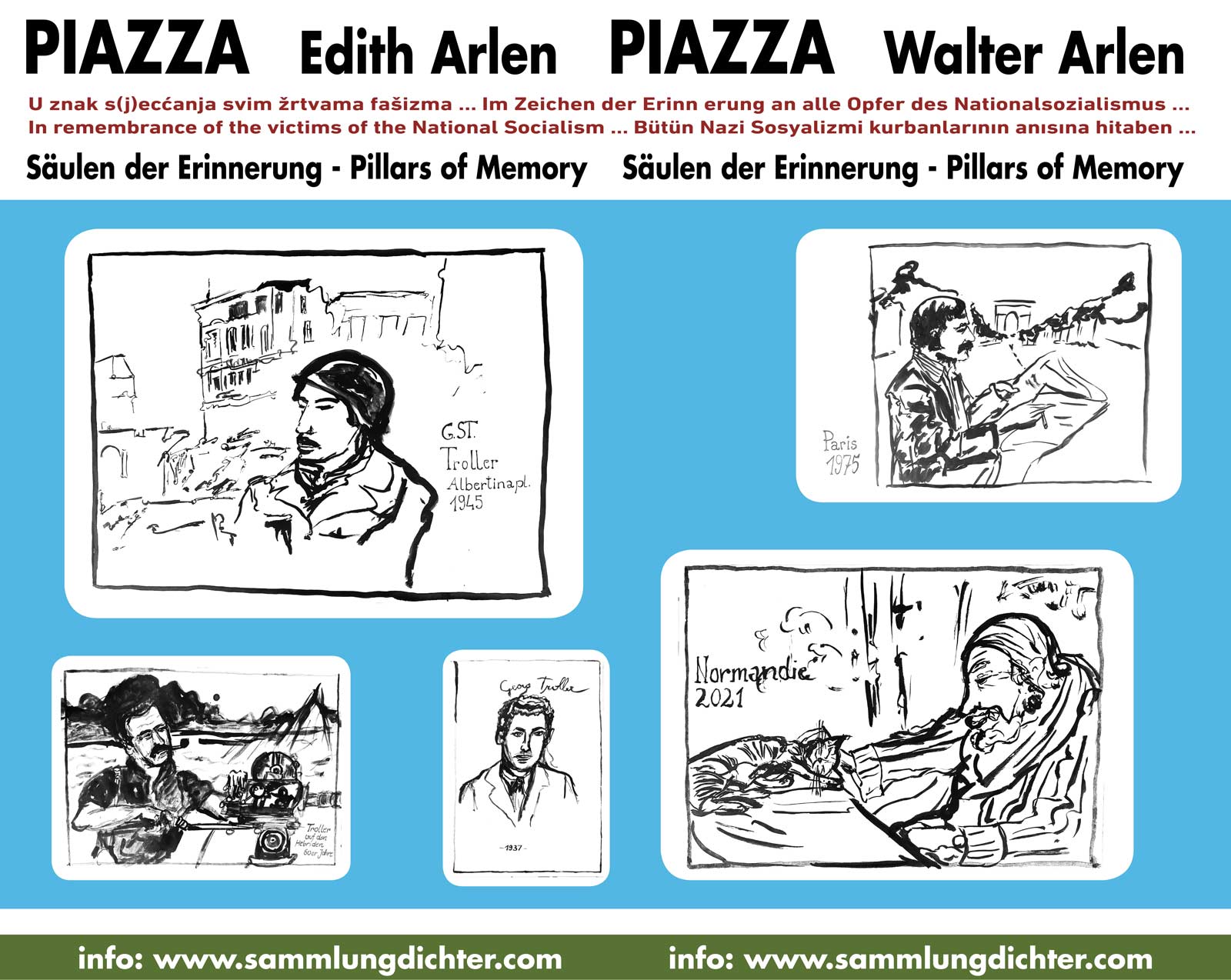

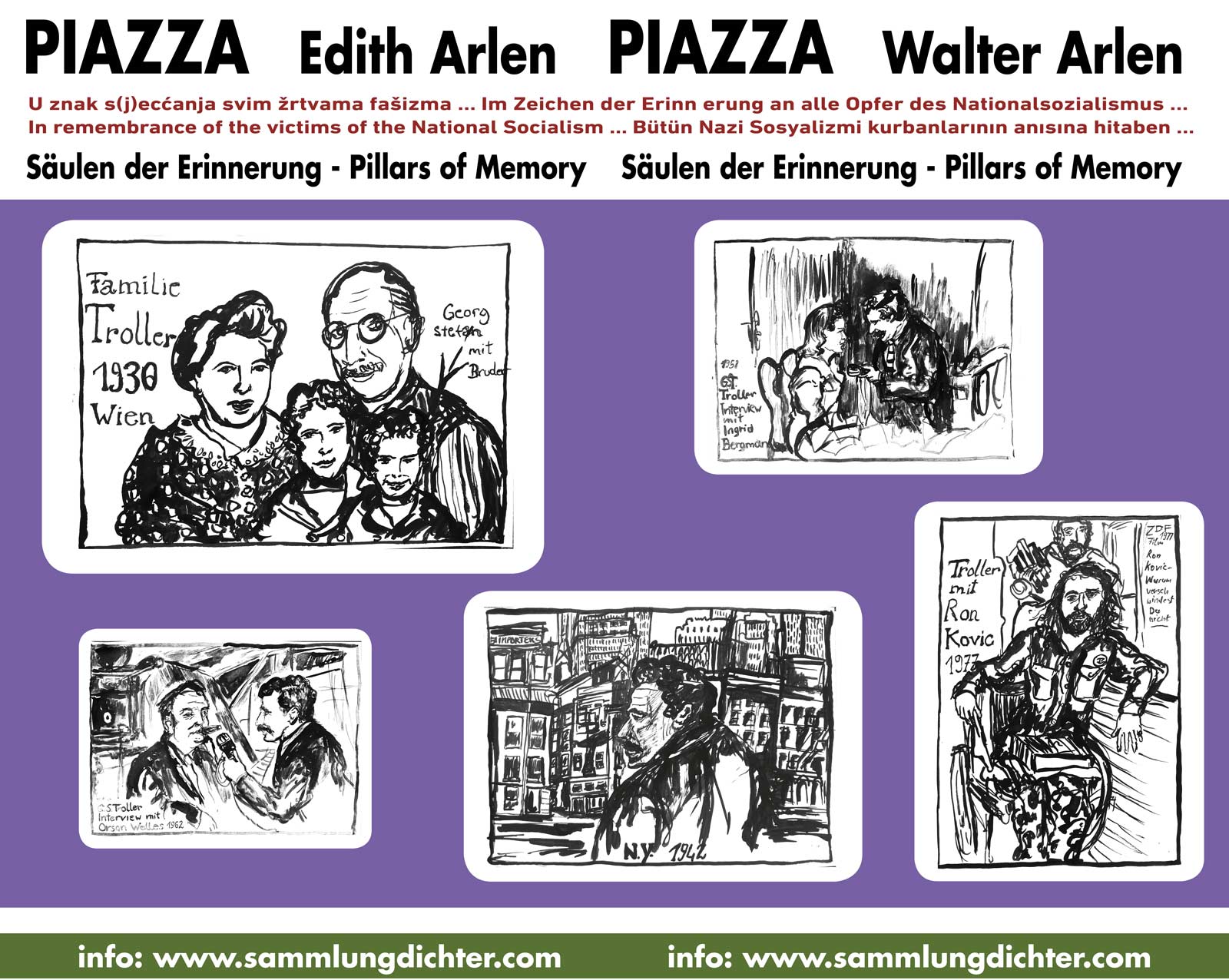

The three advertising pillars on Yppenplatz in Vienna’s Ottakring district were erected in 2008, a result of the “Grundsteingasse” association’s study of the Jewish Dichter family and other “victims of National Socialism” in the following years. And now, in 2021, Georg Stefan Troller, who will celebrate his 100th birthday this year and lives in Paris, is the protagonist of the “Pillars of Memory”. My daughter, the artist Anna Mitterer, visited him in his summer cottage in Normandy in July and provides the images. I myself, as a writer, contribute a text that I wrote for Troller when he was awarded the “Theodor Kramer Prize” in 2005:

60 years ago, Georg Stefan Troller, 24 years old, a corporal in the US army, stood on a Bavarian mountain and looked down into Salzburg, the landscape of his youth. As a reporter for the Munich-based “Neue Zeitung”, published by the Americans, he had a commission to cover the smugglers across the “green border”. And as he looked down into the Salzburg region, a longing took hold of him.

“I had been in Munich for half a year at the time. Well-provided, busy, and among friends. I even had a German girlfriend. What was wanting? At the time, I couldn’t have defined it very precisely, and today, it can hardly be described. What I was wanting was the feeling of homecoming. Of returning. Of a new beginning, no, a rebirth. Basically, a new Troller would have to rise from the new Germany. Too much longing had accumulated in emigration for this comfortable and courted existence as an occupier to satisfy me. I didn’t want to be envied but needed, and (as far as the word was still valid in the world of the living), loved. I was waiting for a call. It didn’t come from Germany. To my immense perplexity, nothing in Germany penetrated into my heart. And at that moment, when I looked down into Salzburg, I knew with an almost desperate hope that it had to be this or nothing. I had declared a hundred times that I had finished with Austria. As with a woman who had disgracefully betrayed me. Even though her seducer later proved to be a dud. Maybe now, she would welcome me at her bosom again? But I had already picked up another, a legitimate bride, so to speak. The one who had paid me for the last three years, who clothed and fed me and had given me her marriage certificate – the citizenship papers. But the truth was that I didn’t want to go back to the legitimate bride. (An impossible truth that I almost kept hidden even from myself.) But that no reasonable call kept me from her … unless: the irresistible call I was waiting for. And the bosom of home into which I might let myself fall, so deeply that no part of me would remain visible.”

And so, Troller went to Vienna and was recruited by the so-called American “theater control”. And visited the old places of his childhood.

“Like all Viennese people, I loved Vienna as ardently at any given time as I hated it, no doubt a fertile situation. The city I had to flee at the age of 17 had never left me indifferent. After all, I didn’t just feel I was a child from Vienna: I was a child of Vienna, a Viennese child. Just as you say Vienna Woods or Viennese schnitzel. This origin, including its specific version of being German, I found myself obligated to all my life, just as much as to the ancestry of my Jewish forebears.”

In Munich, the bombed-out houses had left Troller indifferent; here in Vienna, he laments the smallest gap in the fabric of the streets. For a night and a day, he wanders through the roads in the driving snow. Forgetting his army uniform, reverting to being a child, a Viennese child. Then he stands in front of his father’s business premises in the “Fetzenviertel”, the textile trade quarter – a ruin, a bombed-out shell. He seeks out the apartments of his childhood. In the apartment of a concierge, he discovers his mother’s cherrywood “boudoir”. The father’s library is with the former shop attendant. At officer Fuchs’s, who had meticulously measured the grand piano after the so-called “Night of Broken Glass”, the piano is still there, he had measured correctly. In the last apartment, a small boy sits on the potty, a toy in front of him, a tin puppet. Troller winds up the toy, it beats the drum. The child is glad, it had been broken. “Ah yes,” Troller says, “even then it didn’t work properly, and it cost me five shillings of my pocket money.”

How awkward this is, so terribly awkward. They are afraid of the army uniform. But not of Troller. No sense of wrongdoing. One exception in the last apartment, a man in a wheelchair. In his eyes Troller sees an understanding that all this weighs on him.

At theatre control there is nothing to control. A Thornton Wilder piece is prepared. The director a former Nazi, most actors too. Claudia, Troller’s girlfriend, is the only one without a past. But his boss, Lieutenant Karpeles, shrugs his shoulders. “Who would I make theatre with? With your Claudia as a solo act?”

And with Claudia, things don’t work out either. She wants him to forget, simply to forget everything. “An end to the past!” This phrase already came into being in May 1945.

In spring 1946, Troller travels back to America, leaves the army. The father, still in New York, wants him to take a profession at last: “There are two paths open to you, my son, furs or ready-to-wear.”

For three years’ service in the US army, Troller is entitled to a grant of 10,000 Dollars or a university scholarship for four years. He goes to California and studies English, German, French literature and a whole lot of other things. For the curious, he sometimes is a Parisian, a Scotsman, or a Sicilian. Each time, people say he has the “typical” look of his origin. But some still think he is a Mexican who has crossed the Rio Grande during the night. Why doesn’t he sweep streets or pick fruit? For in California, one is predominantly fair-haired.

“Fair, thin-hipped young gods rode boards through the surf and tumescent fair goddesses happily awaited them on the beach.”

Troller’s platinum-blonde landlady, too, doesn’t have any truck with Europeans: “Someone who only feels at ease when he’s not well!”

Troller needs to get out of there, he tramps South on adventurous paths, following D. H. Lawrence, and in particular B. Traven to Mexico; these are his literary gods. He ends up in Guatemala City, without any money, without papers; the American consul helps him.

And then Troller is back in Vienna again, he cannot help it. He starts with theatre studies, a childhood dream.

“No, no-one insults me. It rains friendliness, even. Now, there seems to be a secret accord with the Jews: ‘We pledge to find you picturesque and traditional from now on; you, Mr. Jew, will in return offer to refrain from sticking our noses into the Hitler filth.’ The Jews – with the exception of the Nazi hunter Wiesenthal – even dutifully kept to it. The others to a lesser degree. The new start generates a society of repression.”

This Troller also realises at the theatre studies department.

“The director is called Professor Heinz Kindermann. Formerly a luminary of racial studies of literature and Nazi roots rhetoric. He even managed to turn Goethe into a Nazi … And again, elections are due in Austria, and now things don’t proceed as meekly as agreed before … An election poster shows the country transected by a deep trench. On the right a goodly man who helpfully extends a plank to the other side. Who does he push out this saving plank for? A national comrade, labelled with the delicate words ‘Nazi problem’. And who is it that throws red filth at this act of neighbourly love from behind? Two Socialist rowdies with Jewish noses. And what is the title of all this? ‘They talk of eternal peace and want eternal hate.’”

Troller leaves Vienna for Paris, the Sorbonne; his application for a scholarship has been approved by the Americans. But before that, he takes his leave. For a whole day, he walks through the autumnal woods, out to Klosterneuburg and beyond.

“No, a second landscape like this didn’t exist a second time in the whole wide world. There was no reason I couldn’t come back to Vienna a hundred times if I felt like it. But never again with the pretence of homecoming. That was over now. Well, that was me done dreaming. But it was not only this dream that had been drained out of me, but dreaming altogether. I mean this state of naďve belief in miracles and invulnerability that had driven me beyond my years, and which had probably also protected me from all perils. And which I now had to shed at last. Not like the colourful butterfly sheds the grey grub. But, so it seemed to me, rather the reverse.”

Paris, not an unknown city for Troller. From Prague, he had fled to Paris in spring 1939, when Czechia was no longer safe. In Paris, and then in the South, the long, unnerving wait for a visa for the crossing to America. The Germans overwhelm France, internment as a suspicious foreigner. Then finally sailing for America, from Marseille. But in Casablanca, a dead end for the present, internment in a desert camp. Two months later finally on the way to New York. And now Paris again.

“When the lecturers deigned to turn up, they didn’t, as in America or Vienna, lecture on subjects their students wanted to study. But on those they were interested in themselves. Or maybe they had been interested in in their distant youths, when literature to them still was liquid fire, not solidified lava.”

When Troller learns that he is supposed to write a Small Thesis of around 300 pages, and a Large one of 1,000 pages thereabouts, he calculates that he will surely have passed his thirtieth year by the time he has conquered this mountain of manuscript that no-one will ever read. And he never crosses the threshold of the Sorbonne again.

As he has already worked with Radio Munich in 1945, founding member number seven of what was to be the Bavarian Broadcasting Company, he applies at the radio station “The Voice of America” in Paris. As a former Austrian, he now also produces contributions to the station “Red-White-Red”, in particular the successful series “XY knows everything”.

This is the beginning of Troller’s rise as a media pioneer in radio and television. After leaving the American radio station, he creates more than 2,000 broadcasting reports for all German stations. For the WDR, he invents the television feuilleton with the “Paris Journal”, which has regular audience ratings of more than 50 %; between 1962 and 1971, he produces 50 episodes of it. Then he is sick of it and wants to engage with people more, with people from all over the world who he is curious about. And this is the origin of the series “Personenbeschreibung” [Personal Description] for the ZDF, 75 episodes from 1972 to 1994. Besides many unknown people (like me, Felix Mitterer, in 1990), he also picks known artists, for instance Peter Handke, Liv Ullmann, Charles Bukowski, Melina Mercouri, Leonard Cohen.

“Admittedly the main purpose of these programmes is to give pleasure to myself. They were called ‘positive’, which probably is due to the fact that I have a rather negative attitude. People remarked on their ‘helpfulness’, and this seems to be based on the fact that they are my private resource of help with life. Regularly they portray people who have pulled themselves from misery by their own bootstraps. People from minorities or with some other disadvantage, disabled or beaten people. How do they manage it, not just to endure, but to overcome? That is what I put up for discussion, what I also asked my interview partners. I ask the things I need to know myself. What usually comes to light in the programmes is that the inner attitude and the personal ideas of people are decisive for their being happy, or their misery. Their fate is in their hands, in spite of everything. Essence comes before existence, also where living conditions play a crushing role. You can lead a much richer life than circumstances seem to allow, than you would believe yourself capable of or you think admissible. You have no chance, use it. You are free.”

That Troller also worked for Austrian television in the end is to do with Axel Corti, the most important television director Austria can boast so far. Troller writes two scripts for Corti, “A Young Man from the Innviertel – Adolf Hitler”, and “Young Freud”, but in particular the great trilogy “God Doesn’t Believe in Us Any More”, “Santa Fe”, and “Welcome to Vienna”. These three films are based on the great autobiography of Georg Stefan Troller, “Selbstbeschreibung” [Self-Description]. All quotes I used in this laudation are from this work, which, I suspect, more than all other books Troller wrote is the motive for awarding him the Theodor Kramer Prize.

That I have hardly used my own words to praise the laureate has a very simple reason: What he says himself is so much more significant than anything I might utter; it speaks for this man by itself, a man who is, although he may not want to hear this, a sage, a teacher, a rabbi.

About the time of emigration, Troller writes:

“So who were we? Exiles? … I never saw myself as an exile. A much too pretentious word for our undignified removal … For the most part, we felt our expulsion to be something final, irrevocable, but this did not help us much in finding our identities. What were we? According to our most intimate feeling: German diaspora. A term that still doesn’t exist today. … ‘The White Horse Inn on Central Park’ in the original line-up. … That’s not Jewish gallows humour any more, here they are already dancing on the rope. While the last Jews are just being liquidated in Vienna, we tearfully sing ‘Call, Call, Vienna mine’ … This was my New York sickness: a paralysis, a grey passivity, a tenacious inaction. I didn’t live any more, I was lived. A shadowy existence.”

All this, Georg Stefan Troller has overcome, left behind. Certainly not without trauma, without scars, these will always remain, how could it be different after all the terror, after all the loss, after all that has been done to him and his family. But his hunger for life was greater. His hunger for love was greater, too. And because he gave love, from person to person, from man to woman, in all his works, it also came to him.

deutsche version